Have we underestimated the development of the PFAS-crisis?

After many presentations during the OECD Global Forum on the Environment dedicated to Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances on 12 and 13 February, this question was discussed. And it has to be said: yes, in a way it probably is.

OECD Global PFAS-Forum: My personal point of view

The two days of the event were incredible and my head is still spinning a week later:

Starting with the PFAS overview, the health consequences of exposure, the global distribution, the complicated methods of analysis, the comparisons of what is being done in which countries. What limit values are there, how long did it take to set them and why are the values constantly being lowered; and how can they be complied with? And what about the waste chains and recycling? What are the consequences and is it even possible to replace PFAS? Anna Lennquist, ChemSec, very emphatically summarised the way forward and concrete offers and assistance with her focus on solutions.

All of this clearly showed how complex, time-consuming, expensive and long-lasting the PFAS problem is overall. "You have to ask yourself where the substances are contained everywhere. And we won't be able to answer this question," said Martin Scheringer, ETH Zurich. He also emphasised that the time factor must also be taken into account in all discussions about the regulation of PFAS, "the PFAS that enter the environment now will remain there forever. It is therefore very urgent to restrict the substances".

The fluoropolymers

The representatives of the fluoropolymer industry took a slightly different view. This was nothing new, because if you follow the previous discussions, fluoropolymers (FP) are safe and there are actually no problems at all.

I found the presentation by Ronald Bock, Chairman of the Plastics Europe Fluoropolymer Group, all the more astonishing, as he repeatedly stated on his slides that FPs are safe, but also emphasised several times during his presentation: "We need to do more". He even agreed with Martin Scheringer that the industry still had some work to do, but that all questions had to be answered by the industry, „we need to do more“. They need to reduce emissions, exchange information on alternative products within their Plastic Europe FP Group, ensure safe handling throughout the production chain, clarify the issue of recycling; the products need to be safe and sustainable. "We have our responsibility and the life-cycle starts with us“.

How does all this fit in with : Fluoropolymers are safe?

During the brief discussion, he also emphasised that the PFAS Restriction Proposal had already set so much in motion that the industry was looking for solutions, but that this could not happen overnight. It will take 5-10 years to look for alternatives and the question is who is prepared to finance this?

I repeat my question: how does all this fit in with: fluoropolymers are safe?

More familiar was the argumentation of Deepak Kapoor, Vice President, Gujarat Fluorochemicals Limited, who emphasised that FPs are safe and are needed. At least the high-end FPs. This is something completely different from FP in carpets or cosmetics, both of which he "threw to the sharks", so to speak: "FP in cosmetics? Please ban them". It was up to politicians to decide which FPs would remain. Kapoor rounded off his presentation with a nice little promotional film about FP. His key message was: it can be managed.

However, I still have questions about the current safety and possible solutions in the future in connection with the mantra: „fluoropolymers are safe“ neither convincing nor sustainable.

Examples of loads

The consequences of decades of global PFAS production for the environment and people are well known, but I still thought it was good that this topic was taken up again in three examples: Central Baden, Flanders and England.

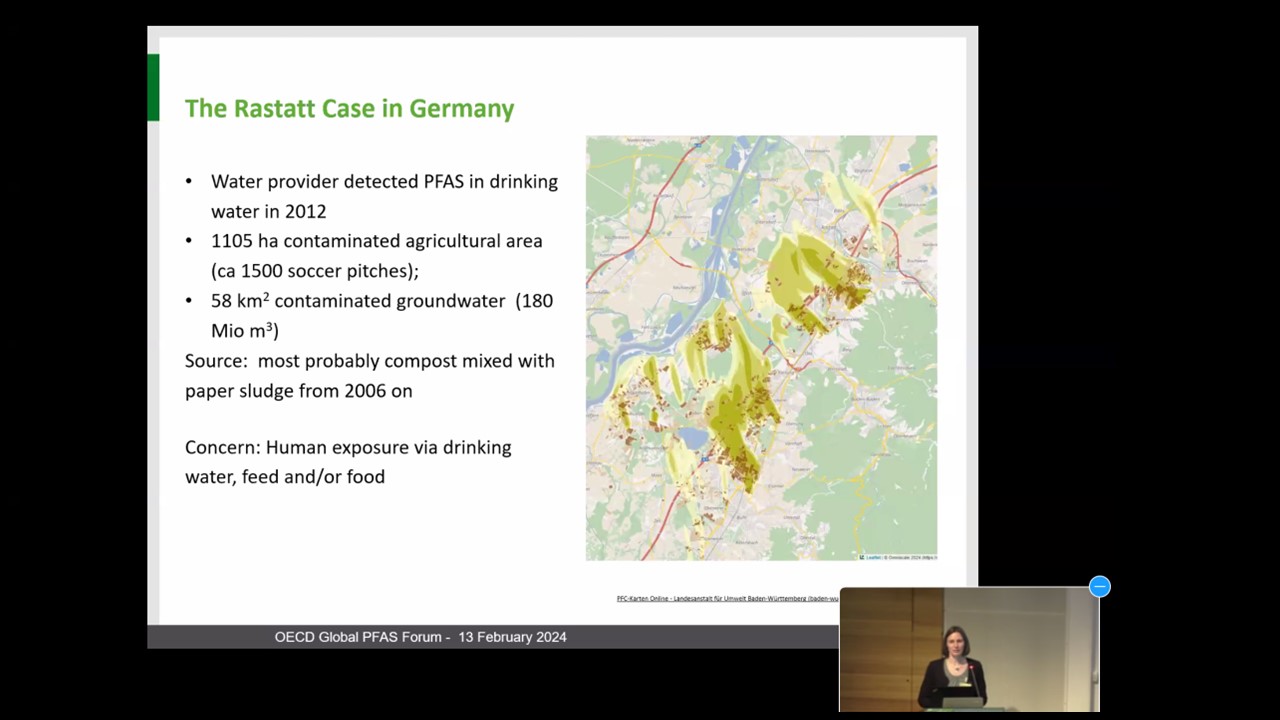

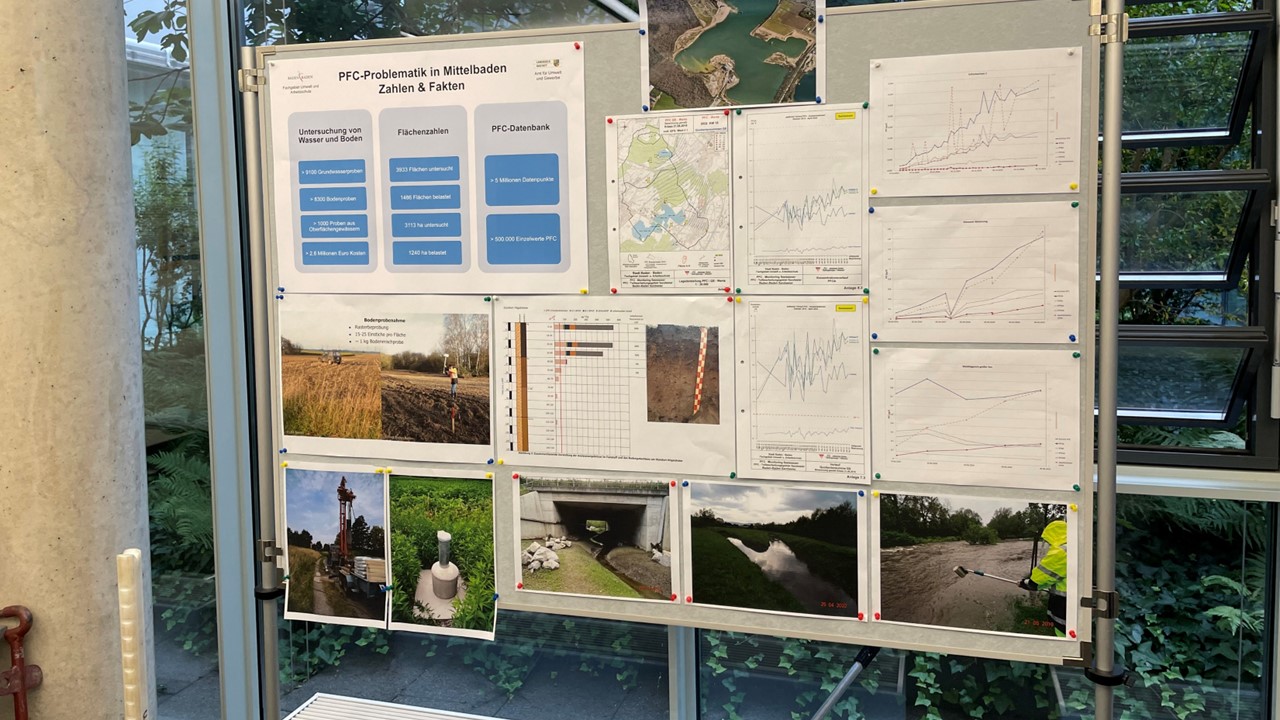

In central Baden there is a small-scale contamination of various fields, which is roughly estimated to be around 27 kilometres long and 11 kilometres wide. A total area of 1105 ha is contaminated by paper sludge compost presumably contaminated with PFAS. The contamination has been known for around 12 years and the region is now living with "PFAS management", as the PFAS contamination in the soil cannot be remediated. The chemicals are still leaking into the groundwater, 58 square kilometres of groundwater are contaminated and all drinking water suppliers have to purify the water. The costs (so far) are around 40 million euros on the open-ended scale.

In Flanders there are two large areas; in Zwijndrecht (3M) and in Willebroek (paper factory), and in England, we were shown the map with the total number of contaminated areas, which included many firefighting areas. All of the cases involved surveys, countermeasures, remediation, testing of water, agricultural products, food and, of course, testing the humans. All complex, all expensive, many questions remain unanswered. Such as the question of responsibility and liability.

"Where do all these substances end up? Where we live," summarised Johan Ceenaeme from Flanders. Factories have been closed for economic reasons and have been converted into residential areas where people now live. The PFAS problem that we know is generally only the tip of the iceberg.

The Forever Pollution Project, a joint European research project by journalists, summarised the European pollution in a map and Stéphane Horel from Le Monde presented the extensive work. They had first spoken to the PFAS experts, then started with the known polluters, mapped the known contamination sites and were confronted with a lack of clarity (how is a PFAS hotspot even defined?). Then they moved on to the possible polluters and industrial activity (have a look at the paper mills), another category was then the "evidence of PFAS-use", so they collected an incredible amount of data. The data is currently being passed on to the CNRS with the aim of compiling a world-wide map of PFAS pollution.

Communication

So PFAS are in us and around us, you would think that everyone talks about them and everyone knows about them. The reality is different: in the public eye, PFAS are often simply equated with Teflon pans and Goretex jackets. If the view of things is so limited, the problem can of course not be understood.

"There is a global use and distribution of PFAS, but there is no global system that summarises or represents this," says Sara Brosché, Science Adviser, IPEN.

The findings of science need to be made available and understandable, and a comprehensible presentation in several languages is needed; "in many countries there is no information about this at all". However, she also emphasised that although information and awareness of PFAS and the problems are important, this cannot be a substitute for regulation.

And I could add to the communication here that as a journalist, you can despair at the very simple requirements of editorial offices. This probably also explains the flood of articles about Teflon pans and Goretex jackets, because everyone knows and understands this

Have we underestimated the development of the PFAS-crisis?

"It's a pollution crisis of the worst kind". Before Horel began her PFAS research, she didn't realise how many affected sites there were. "The impact of PFOA and PFOS on health is very relevant worldwide".

"We measure high levels in the analyses, but we don't know what's really in there and what happens to all the stuff in the environment," says Anna Kärrman.

"I have obtained a lot of data from the studies in the Arctic, where there are neither producers nor users, but there are PFAS. We measure PFAS in blood and it is a relevant global issue and we need to work together," said Amila O. De Silva.

We need international cooperation, we need to share knowledge, harmonise approaches, we need the polluter-pay principle and some kind of responsibility for the clean-up. We need transparency and information, for use, disposal and recycling, we need to avoid PFAS where possible and drive regulation and phase-out.

And in view of the really complex PFAS situation, it would be nice if some politicians or political groups would inform themselves first before making statements, press releases or giving interviews on the subject of PFAS (restriction) - as a confidence-building measure, so to speak 😊⚗️

Internetlink: The OECD Global Forum on the Environment dedicated to Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances

© Patricia Klatt (Text und Fotos)