This interview is part of the student-led Instagram project @perfluorencer, developed as part of the Science – Media – Communication program at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT). Over several months, the team explored PFAS – per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, also known as “forever chemicals.” These substances are found in rain jackets, fast food wrappers – even in our blood. But who's responsible? And how do we get out of this mess?

To find out more, Sarah Moritz and Liz Trupke spoke with Prof. Dr. Hans Peter Arp, environmental chemist at the Norwegian Geotechnical Institute (NGI), professor at NTNU in Trondheim, and lead coordinator of the EU project ZeroPM.

His mission: understanding how harmful substances enter the environment – and how to stop them. Tune in – Arp has a lot to say.

With the kind permission of all involved, I am pleased to share this interview here in the section “PFAS-Gespräche” on pfas-dilemma.info.

From Curiosity to Commitment: The Drive Behind PFAS Research

1. Who are you and what is your job?

Arp: “I am an environmental chemist. I work mostly at the Norwegian Geotechnical Institute, but I am also a professor at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology.”

2. You have been working in environmental chemistry for many years, especially focusing on PFAS. What initially motivated your engagement in this field?

Arp: “Initially, as a student, I was interested in it because it was an interesting chemical with very unusual properties that defied expectations of how chemicals were supposed to behave — or at least how the environmental chemistry community thought they were supposed to behave. Back then, my focus was on solving the puzzles around why they had these unique properties and explaining them better.

My motivation to become an environmental chemist was also to understand how to use chemicals safely, especially after seeing many pollution events. I wanted to learn how science could help prevent or treat pollution. Over time, I became much more interested in that side of it. You have to understand the chemistry to understand the pollution.”

Why PFAS Stay Forever — And Why That Matters

3. How should PFAS be categorized among other toxic chemicals? How dangerous are PFAS compared to other toxic chemicals?

Arp: “The key thing with PFAS is that they are extremely persistent in the environment — more persistent than most other synthetic chemicals. There are a few that come close, but PFAS are pretty much the most persistent of the organic chemicals. That’s important because persistence increases exposure. Many toxic chemicals eventually degrade, so we’re not exposed to them for very long.

But with PFAS, they stick around, so we’re exposed to them much longer. The longer the exposure, the higher the chance that they pose a risk to people or the environment.

4. What are the health risks associated with PFAS?

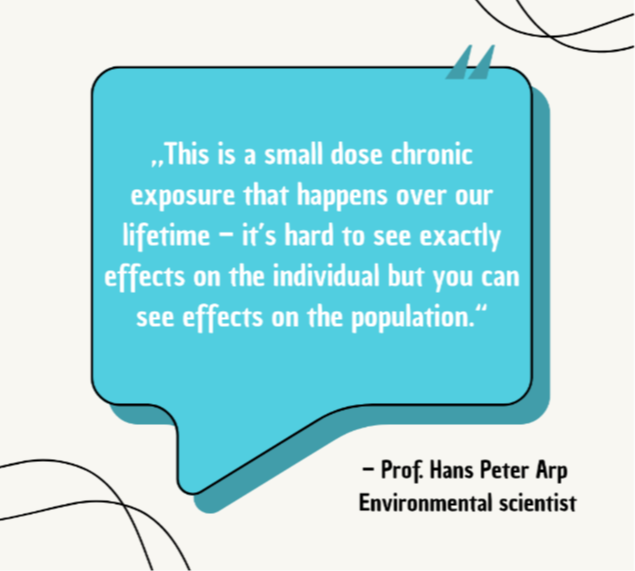

Arp: “When we talk about health risks, we have to remember that we’re exposed to very low doses of PFAS over our entire lifetime. That’s different from an acute spill, where you’d call a poison center. Chronic, low-dose exposure is harder to see at the individual level, but across a whole population, you start to see impacts. It’s like other background pressures — like air pollution or climate change — that can increase cancer rates or lower vaccine responses in some groups. PFAS add to those pressures and reduce overall quality of life in the long run.”

The Long Fight Against PFAS: Persistence, Risks, and Hope

5. How do you assess the current state of PFAS regulation in Europe and internationally?

Arp: “There’s both good and bad news. The good news is that when we first raised the alarm about PFOS and PFOA, regulators and industry acted fairly quickly — especially in Europe and North America — and we could already measure reduced exposures. That showed that if society, industry, and regulators work together, we can cut down exposure to persistent toxic substances.

The bad news is that industry then shifted to other PFAS that often turned out to be similarly persistent and toxic — a kind of regrettable substitution. Now, Europe is leading a more proactive approach with the General PFAS Restriction, rethinking where we truly need these chemicals. The European Union is the most active region on this, especially when it comes to the biggest PFAS like fluoropolymers and the smallest like TFA.

Outside Europe, progress is much patchier. Some U.S. states like California or Minnesota are moving faster, but many others — and most of Asia — are still waiting to see what happens. The real focus now should be showing that early adoption of PFAS-free technology can be profitable too, so Europe can lead by example.”

6. How much do you think the individual can do to avoid PFAS, and how much of the responsibility lies with companies and policymakers?

Arp: “When it comes to PFAS, we should never blame individual consumers. Most people don’t even know if a product contains PFAS — often even the companies selling them don’t realize it. Of course, it is good if consumers avoid PFAS once they do know, and that can send an important signal. But individual choices alone won’t solve the problem. What really matters is that consumers, as a group, influence the market and policymakers. That’s how we create pressure on companies and regulators to take action — not by blaming consumers, but by showing that people care and empowering decision-makers to respond.”

7. What gives you hope in the fight against PFAS pollution – whether technologically, politically, or socially?

Arp: “When it comes to the PFAS problem, we shouldn’t lose hope. I know that hearing about PFAS often feels hopeless and depressing, but as a researcher I also see positive changes. There are real examples of progress, and many people are genuinely motivated to find solutions. Being part of a community like ZeroPM, surrounded by solution-oriented people, gives me hope. If you ever feel discouraged, reach out to NGOs, scientists, or others working on the front lines — seeing their commitment reminds you that positive change is still possible.”

Prof. Arp, thank you very much for the interview.

Interview conducted by: Sarah Moritz, Liz Trupke, June 3, 2025

Instagram-channel of the KIT-students: @perfluorencer, (https://www.instagram.com/perfluorencer/ )